Lighter & Princess star Arthur Chen lands in hot water after a private affair exposé

Lighter & Princess star Arthur Chen lands in hot water after a private affair exposé

Caution: Minor spoilers ahead.

It’s ironic, isn’t it? The contemporary world people currently live in? Anything deemed worthy and real is superficial and the truth is merely as big as the size of the shoe whose foot it fits, such as in Akuma to Love Song’s drama adaptation.

Such flippancy and an endless array of likes in character deficiency are annoyingly degrading but it does match superbly well with the sheep mentality where people follow others rather than themselves for an ingrained need to fit in and avoid loneliness at all costs. It's akin to a cute pink strawberry coated in a mint chocolate of stupidity paraded on top of a pristine white cake of affirmation. That visual image is so utterly beautiful it almost seems shameful to want to eat it, right? But what if the strawberry was enhanced with chemicals to make it gorgeous? What if the chocolate was produced in sub-human conditions and the workers paid peanuts? What if the cake was packed with gluten? Would someone still want to eat it? Would someone still eat the cake and admit it, or hide it to keep up with the Joneses?

It is apparently easier to feel special in a Truman Show illusion where fake roses mask a green garden of weeds than to live outside the box, in authenticity, and bloom solely amongst a select few. After all, being real is not for the fainthearted and actually requires thinking. Being fake, insecure, and practicing self-pity on the other hand requires very little effort as it is not backed by any substance whatsoever.

The “please be kind” and mindful not to be offensive with personal bluntness and thus verbally abused by self-righteous moronic idiots who deem themselves the enforcers of truth and the Robin Hoods of the “believed oppressed” is more often than not a result of low self-esteem and belief that criticism is destructive. The word, however, is more than the ignorance of attributes one credits it with. That deep sense of apparent injustice reveals the concept as a personal affront, expressed through an exquisite haute couture egotistical need to retort quickly, instead of pausing to actively listen, to assimilate what is being communicated and then make a choice: to voice a comment or to voice silence. If a person is negative and perceives the bad, then thought it might be bad, it might also be good. Life is not always strawberries and cream. It is also a gingerbread latte, an espresso, a pistachio Frappuccino, a peppermint hot chocolate, and sometimes a spicy chocolate mocha cayenne. It depends on the day and of course Starbucks' location.

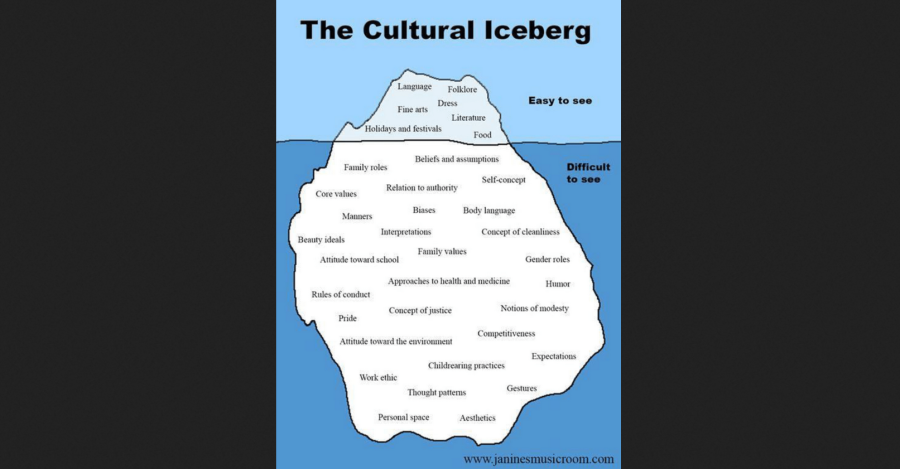

Akuma to Love Song is a drama adaptation of Akuma to Rabu Songu, a 13-novel shōjo manga created by Miyoshi Tomori in 2007. Produced by Hulu in 2021, the series befalls under the “lonely student” category of Japanese television visual productions, of which there are few. However, rather than following Disney and venturing into cliché DNA sea waves, the story breaks the mould by going beyond the literal confrontations amongst classmates to poke deeper into the self and the inner battles one has with their dark side if solely scratching the surface of what the manga does in detail. This is a vivid example of Edward T. Hall’s superficial culture, a component of his iceberg theory, where deep culture remains concealed under that “veil of shallow reality”; a social media greenhouse matrix that grows fickle disposable levity breathing substantial frippery instead of plants that provide oxygen to human beings.

8 episodes of insufficiency are allocated to the portrayal of character peripherical psychological layers with an underabundance of flair in a rushed pictorial movement of opaqueness that rather than effervescently rabble-rousing the audience into an ecstatic euphoria wouldn’t agitate the nervous system out of a sinus rhythm. Fundamentally, the cerebrum is left wondering the whereabouts of added imaginary episodes in the unmaterialized expectations of drama fans to make Akuma to Love Song superior to above average.

The drama alienated clarity to the point of oblivion, questioning the meaning of emotional intelligence, such were the series' idiosyncrasies and the heavy absence of emotional clarity across the production, overcompensated by significant deviations from the manga.

The story remaining female-centric is a relief. It focuses on an adolescent named Maria Kawai who was expelled from a prominent Catholic school run by nuns for hitting one and was forced to enroll at Touzuka High School, a public school with lower educational standards. There she builds relationships with two same-age teenage boys, Yūsuke Kanda, and Shin Meguro, and develops a group of girl-friends that comprises Tomoya Kōsaka, Hana Ibuki, and Ayucchi Nakamura as time progresses. This is what both the drama and the manga have in common, delving deep into Carl Jung’s shadow theory, despite the series not exploring it as profoundly as the manga. Through her bluntness, assertiveness, and honest mannerisms Maria ignites annoyance around her, while also provoking an eruption of consciousness in her to-be quintet of close friends, compelled to confront their own fears and the darker side of their personalities, repressed, locked away in a guilt-laden objection to being. A person’s shadow is not their enemy as Maria implies through her words and conduct but it will fester and grow if not dealt with, becoming cataclysmically gloomier as linear time perceptively transcends into an existing stochastic process, which is in fact reality. The idea that inner darkness might be the reason for one’s suffering is merely a result of an inability to deal with it and to acknowledge the presence of light within the self.

Maria is an unparalleled vocalist who carries a Celtic cross around her neck, given to her by the nun she had a physical altercation with, a detail not mentioned in the drama, firmly focused on her promises and her love for Schubert’s Ave Maria, a Roman Catholic singing prayer to the Virgin Mary.

The series does, however, depict Maria slapping the nun on the face in lieu of her attitude towards the bullying that Mizuno Shiori was enduring at the school (to be clear, by choice), not mentioned in the original work, and Maria’s guilt for breaking a promise to her mother as a child and consequently causing her mother’s early death and her family’s disintegration. These actions are dubiously questionable. A Catholic nun carrying a Celtic cross with her in the manga (one that is attributed to paganism) and outwardly ignoring bullying in the drama exemplifies the behavioral hypocritical traditionalism of the Catholic Church in a number of issues, out of tune with modern society.

Deep inside, Maria wants to fit in, make friends, and belong, but not at the cost of losing herself and her core essence as a human being. It would be easier to join the crowd, but if she did, she wouldn’t be Maria. Standing one’s ground against the masses is an act of courage and madness at the same time, but the reward of sticking up for what one believes despite being different from everyone else is a breath of fresh air imbued with leadership. The lion might be the king of the jungle but the wolf does not perform in a circus. Maria, rather than standing up for others, forces them to confront and stand up for themselves, attracting foes turned into lasting friendships for her and proving that true friends will eventually turn up without the need to compromise oneself to fit in a societal group, whatever it is. This is quite original considering dramas' tendency to often portray contemporary savior attitudes popularized during The Crusades with strong characters saving weaker ones, who will go on to develop an “admiration/gratitude life-long puppy complex”. Akuma to Love Song takes the road less traveled with Maria giving a select number of her classmates the tools to defend themselves or help them stand their ground.

Meguro is a talented piano player with an inferiority complex caused by being the male child of a prodigy musical conductor. He has enjoyed playing the instrument since he was a child, however, the pressure of being his father’s son caused him to feel frustrated during his performance debut when he was younger and call it quits. A career in classical music would always draw comparisons with his genius maestro father, but as a child, he lacked the emotional and social skills to deal with it.

As a child, the label sucked him into a primary inferiority complex by supplying Meguro with the motivation to excel to the point of breaking him and amplifying his inferiority complex further as an adolescent; a secondary inferiority where Meguro felt that he could never be great at playing the piano. Meeting Maria at school challenged all of that and the highly introverted, unsocial teenager was naturally and unintentionally persuaded to open up to her, growing fond of her blunt straightforward personality, and eventually falling in love with her.

Through Maria’s love for singing, Meguro re-discovers within himself his courage to love music again without fear of failure and his raw, unparalleled drive to pursue his aspirations and become his own man, his own person in his love for himself, in his love for the piano and in his love for Maria. Meguro, whose name draws light to the same name river in Tokyo, allowed himself to feel the flow and see where it took him. He enters a competition playing the compulsory piece Ballade No 1 in G minor Op 23 then moving on to a masterpiece rendering of Liszt 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S. 558 – Ave Maria (558 is a collection of 12 songs penned by Franz Schubert but adapted by Liszt for individual piano play) that would win him first prize and the opportunity to pursue his academic studies abroad.

Yuusuke Kanda feels like comic relief throughout the series. He is bubbly and cute and friendly and he gets along well with everyone. He is also a good son to his ill, frail mother but despite his positive attributes he only stands out for his first name, Kanda, another river in Tokyo, and for defending and protecting Maria.

He is loyal and kind and while these soft qualities could represent a lack of a backbone and portray him as a spineless boy, they actually illustrate how strong and resilient he is. Kanda is like a tight knot that binds everyone together in friendship and love. In a present world imbued with cynical, hypocritical, and fastidiously smoke and mirrors, it is heartfelt to see a character that is warmly warm for the sake of just being who he is.

The casting was spot on with the leads, although curiously enough, the leads can be debatable with the manga giving predominance to Kanda instead of Meguro while the drama going full on with the latter, following the trend of not challenging the status quo in what concerns to “true love” between those in a romantic relationship or at any stage leaning towards it.

Asakawa Nana as Maria and Iijima Hiroki as Meguro were also meticulously accurate. Nana was strong, solid, and convincing in her “rendition” of Maria but while excellent it was not mesmerizing. Hiroki, on the other hand, conveyed such an array of emotions as Meguro, particularly when playing the piano in his sadness/longing for Maria which was heart-wrenching, exquisitely raw, and utterly enthralling. His facial expressions in Akuma to Love Song give vibes of Kento Yamazaki’s plethora of expressive nuances where he consistently and continuously exhibits semblance brilliancy, hard to construe beyond a bewildering beguiling contemplation. Reynold Poernomo comes to mind with his highly inventive creative work. While Nana’s performance would be “the golden snitch”, Hiroki’s would be “down the rabbit hole”. Between the complexity and hard work of the two, however, Alice in Wonderland wins. Okuno So’s performance as Kanda was a standardly good “cassis plum” albeit it wasn’t a pressure test, nor was it a show-stopper, lacking impact, with an incessantly merge into the background. It was enough. It served its purpose. It just wasn’t a “forbidden fruit”.

Through the love/reason dichotomy, the drama is an ode to being real, true to oneself, following inner light and guidance, and living, rather than being content with a meager paltry existence corroborated by artificial likes and online avatars permeated with the opinions of others. At the same time, the epode equally appeals to the union between the emotional and rational sides that comprise a person in a heterogeneous environment, both internal and external, adding flair and style to what can be perceived as a wishy-washy dull entertainment piece.

Overall, Akuma to Love Song was a “greenhouse” cultivation with additives to improve the appearance and quench the audience's thirst for a “tasty” albeit fake visual production. Had it been organically developed without artificial enhancements, the quality of the series would have been better and genuinely real.

| Credits: Images are linked to their sources. | Edited by: devitto (1st editor), BrightestStar (2nd editor) |