"Who can throw a stone?"

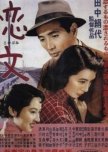

Love Letter was actress Tanaka Kinuyo’s first film to direct. WWII was over and the censors had left so she could address sensitive issues about American G.I.’s having Japanese lovers. The subject for her first film was a tough one and the 1950’s attitude of the male lead was difficult to sympathize with.

Five years after WWII, Reikichi lives with his younger brother, Hiroshi, who pays most of the bills. An old friend brings him into his business translating and writing love letters in English for women who have been involved with American soldiers. Most of the women are asking for money and Yamaji makes the letters flowery and eloquent. Reluctantly, Reikichi begins work there to bring in more money. He’s despondent because he has never forgotten his first love who married someone else. When he discovers that she’s a widow he goes to the train station every day to search for her. As luck would have it, she comes into the shop to have a letter written to an American soldier who had fathered her baby.

First the positive. I enjoyed Tanaka’s fluid directorial style. Despite the year and cultural values, she showed Michiko in a mostly sympathetic light. Mori Masayuki gave a wonderfully complex performance, even when I wanted his character to erupt in flames. Yuga Yoshiko brought a damaged, yet sweet spirit to Michiko. Michiko was a woman who had lived through her own hell and was still able to be kind to others. The supporting characters were also strong. Tanaka made a guest appearance as a woman needing a letter written by Reikichi but instead received an earful about her lifestyle from the sullen man.

Much was made of Reikichi’s loyalty in waiting for Michiko for five years. They made a point of him standing next to the Hachiko statue, the dog who had waited faithfully for his deceased owner every day at the station for nearly 10 years. For Michiko to have sullied herself with a foreigner from the country that had defeated them was too much and the diatribe Reikichi buried her in was vile. That she’d also given birth to a “blue-eyed baby” who had died made her acts even worse. He knew nothing about her and the struggles and pain she had faced. He was unable to comprehend that the man she’d been involved with had been what she needed at the time. This kind of overly precious attitude about women’s virtue struck me as false given the horrors the Japanese military committed against women during the war.

What saved this film for me was that both Hiroshi and Yamaji called Reikichi on his stupidity and stubbornness. “Who do you think you are? A saint? You can’t be proud of the way you lived.” They knew that the war years and post war years were brutal for women, especially single women without a family to support them. For Hiroshi, Michiko’s actions could be forgiven as she had only been with one guy, unlike the prostitutes who made a living off the white bread foreigners. Michiko was a kind and elegant women who condemned herself for being “depraved” which was awful to hear. Reikichi wasn’t exactly a great catch. Though well educated he’d been sponging off his brother since he came home.

Japan had much to process after the war. Soldiers had experienced traumas and civilians had lived through their own. Most people had either visible or invisible battle scars. Reikichi was learning the hard way that forgiveness was hard to come by and sometimes harder to give when clinging to rigid ideals.

30 August 2024

Five years after WWII, Reikichi lives with his younger brother, Hiroshi, who pays most of the bills. An old friend brings him into his business translating and writing love letters in English for women who have been involved with American soldiers. Most of the women are asking for money and Yamaji makes the letters flowery and eloquent. Reluctantly, Reikichi begins work there to bring in more money. He’s despondent because he has never forgotten his first love who married someone else. When he discovers that she’s a widow he goes to the train station every day to search for her. As luck would have it, she comes into the shop to have a letter written to an American soldier who had fathered her baby.

First the positive. I enjoyed Tanaka’s fluid directorial style. Despite the year and cultural values, she showed Michiko in a mostly sympathetic light. Mori Masayuki gave a wonderfully complex performance, even when I wanted his character to erupt in flames. Yuga Yoshiko brought a damaged, yet sweet spirit to Michiko. Michiko was a woman who had lived through her own hell and was still able to be kind to others. The supporting characters were also strong. Tanaka made a guest appearance as a woman needing a letter written by Reikichi but instead received an earful about her lifestyle from the sullen man.

Much was made of Reikichi’s loyalty in waiting for Michiko for five years. They made a point of him standing next to the Hachiko statue, the dog who had waited faithfully for his deceased owner every day at the station for nearly 10 years. For Michiko to have sullied herself with a foreigner from the country that had defeated them was too much and the diatribe Reikichi buried her in was vile. That she’d also given birth to a “blue-eyed baby” who had died made her acts even worse. He knew nothing about her and the struggles and pain she had faced. He was unable to comprehend that the man she’d been involved with had been what she needed at the time. This kind of overly precious attitude about women’s virtue struck me as false given the horrors the Japanese military committed against women during the war.

What saved this film for me was that both Hiroshi and Yamaji called Reikichi on his stupidity and stubbornness. “Who do you think you are? A saint? You can’t be proud of the way you lived.” They knew that the war years and post war years were brutal for women, especially single women without a family to support them. For Hiroshi, Michiko’s actions could be forgiven as she had only been with one guy, unlike the prostitutes who made a living off the white bread foreigners. Michiko was a kind and elegant women who condemned herself for being “depraved” which was awful to hear. Reikichi wasn’t exactly a great catch. Though well educated he’d been sponging off his brother since he came home.

Japan had much to process after the war. Soldiers had experienced traumas and civilians had lived through their own. Most people had either visible or invisible battle scars. Reikichi was learning the hard way that forgiveness was hard to come by and sometimes harder to give when clinging to rigid ideals.

30 August 2024

Vond je deze recentie nuttig?

55

55 204

204 11

11